Downwind Paddling Technique

Disclaimer: I don’t have downwind experience in the big ocean conditions, what I write about below is based on experience primarily in Grand Traverse Bay of Lake Michigan and occasionally on open Lake Michigan. Six foot swell is probably the largest conditions I have seen. I do suspect that the fundamentals hold true regardless of wave size.

Everyone Needs to Experience Surfing Swells

The more I paddle downwind the more convinced I am that if everyone could experience linking two or three waves together on a downwind run, surfskis would sell themselves. In my experience there aren’t too many experiences that feel as good as linking multiple waves together and watching your speedometer jump as you cruise effortlessly, scanning for the next big opportunity.

I know many surfski paddlers have tried to describe in words and to show with excellent video set to music, the feeling of a nice downwind run, but like anything, until you truly experience it for yourself, it is hard to understand. One thing is for sure, pictures and video can never due justice to the size and energy of the waves that you feel when you’re immersed in them.

One analogy I like to use with bikers and skiers is that imagine if the terrain you were on was constantly changing and by reading it correctly and timing your sprints, you could actually create your own down hills. So imagine a downhill moving in front of you and you’re chasing it, knowing once you catch it, you’ll get some nice additional speed and a breather. The net effect is that you find yourself one hundred percent immersed in the moment, absolutely present, and putting in maximum efforts without even noticing it. The best interval workout there is, bar none! I am routinely amazed when analyzing my HR stats after a downwind run and seeing that I was close to my max HR for a large percent of the time without ever realizing it.

Expect a learning curve

It certainly has not always been so blissful for me. There is a definite learning curve to truly linking waves, not having a coach or anyone else to paddle with and point out everything I was doing wrong, it took me a lot of trial and error. I really just started getting it dialed in late last year, the end of my 7th season paddling a surfski. For the longest time I was convinced that the waves on the Great Lakes and specifically West Bay where I do most of my paddling, were simply to steep and stacked to effectively surf with a surfski. While part of me was convinced of this, I also knew that if one of the surfski legends was to come out and paddle with me, they would find a way to work the chop and show me how pathetic my skills were. I am happy to now declare that I have come to the full realization that there is really no such thing as too steep or choppy of waves for downwind paddling in a surfski. It all comes down to developing the skills to read the water, position the boat, and time the application of maximum power to catch the wave and then ride it correctly once you are on it.

I can tell that I have made some significant improvements in my downwind paddling as my average speeds in downwind conditions have increased significantly. In the last few years my fastest downwind miles were typically in the 7.5 mph range. Now I am seeing averages just above 8 mph in relatively small conditions (2 foot swell). It has now become rare for me to get into a full stall where I come to a dead stop and swamp the cockpit, whereas in the first several years this was a common occurrence.

Below is a list of key elements I’ve learned through studying every piece of downwind literature I could find on the internet and lots and lots of trial and error:

- Consistent Speed is Critical – The name of the game in downwind paddling is to get your boat up to the speed of the swell and hold it there. Speed begets speed is the mantra. In order to quickly generate speed in a surfski you have to have a solid forward stroke and the confidence in your boat to apply maximum power with everything you’ve got. This is where it pays to get a boat that is plenty stable for your skill levels. In many cases the most critical time to apply max power is when you are perched on top of a wave with half the boat out of the water. In the wrong boat this can be quite a scary feeling, but with the right boat you’ll have all the confidence you need to put the hammer down In my experience on Grand Traverse Bay, the swell is typically moving around 7+ mph. If you aren’t moving at that speed then the waves are passing underneath you. As the waves pass underneath you will oscillate from a bow up stalling position to having the bow drop down behind the wave and submerge in the trough. This may make you feel like you don’t have enough volume in the bow or you’re your boat is too long, etc. but the real culprit is that you aren’t carrying enough speed. Once you can link a few waves and get your speed up with the swell the entire landscape of the water changes and it no longer feels choppy. Rather it feels much smoother and you begin to see the waves forming in front of you and it is easier to stick your bow right behind them as they form and sort of draft the forming wave as it rolls out off the front of your bow.

- Perpendicular to catch the wave, but not to ride it – This was probably the hardest concept for me to come to terms with. For my first 5 years of paddling I just couldn’t get away from the tendency to want to run straight down the wave at a perpendicular angle. I attribute much of this to thinking this would give me the maximum speed and also being afraid to broach (turn the boat sideways parallel to the wave and tip over). The reality is that you do need to be perpendicular to first catch the wave, but once on it, if you don’t cut across at an angle you will eventually knife into the wave in front of you and stall the boat in the trough. This might be nice if you’re hot and want to cool down (the wave behind you will crash over you and swamp the cockpit) but it brings you to a complete stop and you have to work very hard getting the boat back up to speed. The other reality is that as long as you are carrying speed as you angle across the wave, you are not likely to broach. The speed will keep you very stable.

- Play with the Angles – A downwind paddle ends up looking more like a zig zag than a straight line. It is important to play with the angles/direction to find what is working best for you on any give day. The conditions are always a little different. I tend to get stuck working my runs to one si

de, but unless that is working great for you and you’re aren’t experiencing any stalling, I would suggest trying to mix the directions and keep working until you find the sweet spot - Bow Up Paddle Hard / Bow Down Recover – The general guidelines are when your bow is up you are stalling and need to apply a lot of power to get the bow down and the boat running on the wave. This does hold true, but in addition, there are times when you just need to let the wave pass underneath and let the bow naturally drop down and then start your sprint to catch the wave. You can waste a tremendous amount of energy and effort trying to paddle up the back side of every wave that passes underneath you and gain very little. Timing is critical. And like direction, this is something to continuously experiment with as you are learning

- Overcoming waves in front of you – As you paddle downwind you are constantly assessing the waves in front and to the side of you and making decisions on when to stay put and when to sprint forward. If the speed of the wave you are on is good and you’re feeling comfortable with it, you should ride it as long as possible. However if you have the opportunity to carry your momentum ahead and jump forward a few waves that can really help build your speed. As with all aspects of downwind paddling, the more you experiment with overtaking waves, versus holding back, etc.. the stronger your instinct will develop and you will naturally make the right decisions.

- Light Bracing/skimming the paddle – Unless you really need to brace for stability, I would recommend that you just keep your paddle moving so you can quickly put in another acceleration when needed. I am finding that in the smaller conditions that I typically paddle in, this is definitely optimal. On small waves you shouldn’t need the added stability of a brace but the waves are moving quickly and the runs are shorter so you do need to do more continuous paddling

- Linking Waves Together – It is relatively easy to catch a single wave, but to smoothly transition/link from one run to the next is where the real skill comes in. This is where I find myself still struggling at times. You will notice right away if you have a good run on a wave, but then don’t sprint forward to another or correct your angle to catch the next one. You will find yourself trying to catch the next wave at an angle and it just won’t work. The bow will raise up and although you may not be in a full stall you will get some water in the cockpit as you waffle on the wave. One of the keys to avoiding this is to not let up on your paddling effort and use the speed you gain on a run to ensure you are solidly on another wave before letting up.

- Picking the right wave – In larger ocean conditions I know this is absolutely critical. In smaller choppy conditions I think the concept still applies, but because the waves are more frequent and the runs shorter, it seems to me that you have a little more margin of error for picking waves. I have noticed that at least in Grand Traverse Bay the waves tend to run in sets of 3. So if you see a big one underneath passing underneath you, you can be pretty confident there are two more right behind it

Summary

Downwind paddling is addicting. Obviously the bigger the conditions the longer the runs, the faster the speeds, and the bigger the adrenaline rush, but by no means should you discount the fun and challenge that can be had even in small 1 ½ – 2 foot waves. You can be certain that the pros will milk every ounce out of any perceptible water movement when they are racing. It is in your best interest to practice the same. Never get into the mode of just grinding away assuming the waves are too small to surf. If you are going downwind constantly read the water and play with your positioning and try to leverage whatever water movement you can. It definitely helps to have a GPS displaying your speed to keep you motivated. As anyone who has paddles knows very well, speeds on the water can be very deceiving.

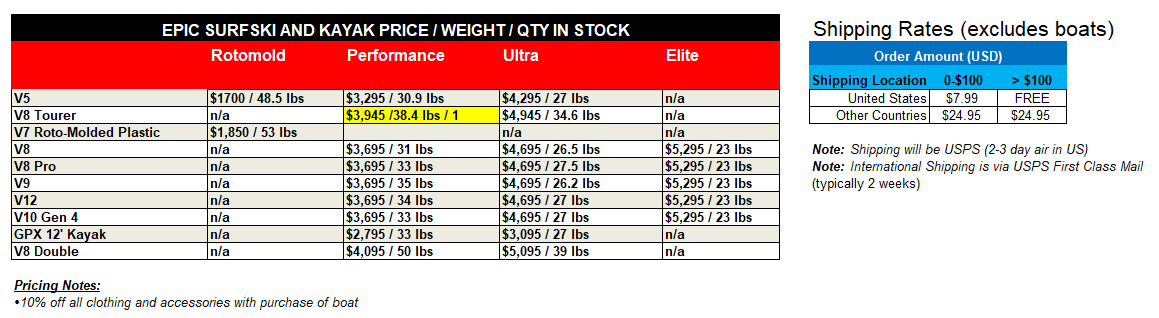

In Northern Michigan we are very fortunate to be surrounded by so much water. As my downwind addiction has grown and I’m scanning West Bay every minute of every day, I’m realizing that there are very few days when we can’t get out and find some waves/chop on either the bays or the open lake. It really doesn’t take much wind to generate a decent wave pattern, a solid 7 knots and above is usually good. My mission with my customers is to do everything in my power to get them experiencing surfing waves because I know once that happens they’ll be huge ambassadors to help grow the sport of surfski. It is an addiction you can’t easily quit, but that is a good thing. There aren’t too many other activities where you can get an incredible adrenaline rush along with a phenomenal functional/core/max power workout in combination with a maximum anaerobic effort all while being so consumed in the moment that you don’t even notice the pain.